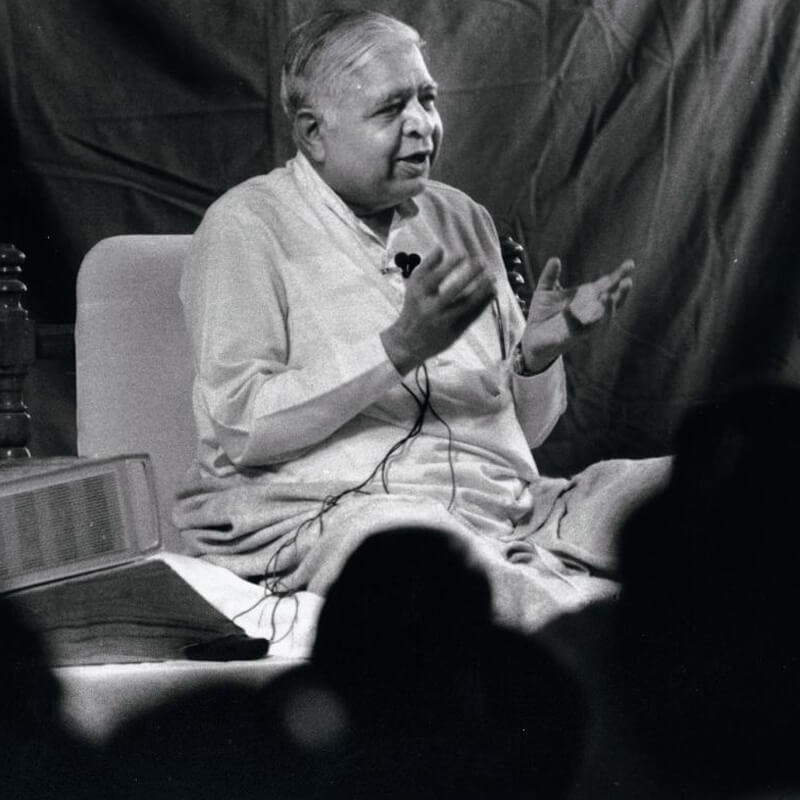

(Following public talk was given by Mr. S. N. Goenka at Hyderabad, India in 1993)

Note: The Sanskrit word Dharma (which is spelled Dhamma in the Pāli language) originally meant “the law of nature” or “the truth.” In today’s India, unfortunately, the word has lost its original meaning, and is mistakenly used to refer to “sect” or “sectarianism.” Using this theme as an introduction, Goenkaji explains that Vipassana meditation teaches how to live a life of pure Dharma—a life full of peace, harmony and goodwill for others. This subject is particularly relevant in India today—and indeed the whole world—where sectarianism and communalism have divided large sections of society and caused acute suffering.

Friends, seekers of peace and harmony:

Everyone seeks peace. Everyone seeks harmony. Life is full of misery, misery of one kind or another, due to this reason or that reason. There is misery everywhere. How can we come out of misery? How can we live peaceful, harmonious lives, good for ourselves and good for others?

The sages, saints and seers of India—the wise, enlightened ones—asked: "Why is there misery?" and "Is there a way out of misery?" There are innumerable apparent reasons why there is misery. But we cannot come out of misery by eradicating these apparent reasons. The real cause of misery lies deep within ourselves. And unless this deep-rooted cause of misery is eradicated, we can never experience real peace, real harmony or real happiness.

How can we eradicate the deep-rooted cause of misery within ourselves? Everyone who was wise and enlightened realized that the only way to eradicate misery was by following the path of Dharma. If one lives the life of Dharma, one is definitely coming out of misery. Dharma and misery cannot co-exist. But the difficulty came when, after a few centuries, people forgot what Dharma was. When one does not understand the real meaning of Dharma, how can one apply Dharma in life?

Two thousand years ago in India, there were two distinct traditions. One tradition gave importance to the purity of Dharma. The other gave importance to sectarian rites, rituals, religious ceremonies, external appearances, and so on. In those days, the tradition of pure Dharma was quite strong, but slowly it became weaker and weaker, and eventually vanished from India. What was left had no trace of pure Dharma. It is very unfortunate that we have lost Dharma. When one speaks of Dharma in today’s India, the question that arises in the audience’s mind is: "Which Dharma? Hindu-dharma, Buddhist-dharma, Jain-dharma, Christian-dharma, Muslim-dharma, Sikh-dharma, Parsi-dharma, or Jewish-dharma? Which Dharma?"

It is a great pity that we have totally forgotten pure Dharma. How can Dharma be Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Jain, Parsi, or Sikh? This is impossible. If Dharma is pure Dharma, it is universal. It cannot be sectarian. Sectarian rites and rituals differ from one sect to another. The so-called "Hindu-dharma" has its own rites, rituals and religious ceromonies; its own beliefs, dogmas, and philosophies; and its own external appearances, and disciplines, such as fasting. It is the same with the Muslim-dharma, Christian-dharma, Sikh-dharma, and so on. But Dharma has nothing to do with all these. Sectarianism is divisive. Dharma is universal: it unites.

The meaning of Dharma in the ancient language of India has been lost.

Unfortunately, our country has lost the bulk of its ancient literature and scriptures. This literature was preserved and is still being maintained in the neighbouring countries. When we study these writings it becomes so clear what the people of this country meant by Dharma in ancient times. The definition was "Dhāretī ti dharma"—what one holds, what one contains, is Dharma. This means what one’s mind is holding, what one’s mind is containing, at this moment. These contents may be wholesome thoughts, or unwholesome thoughts. In the language of those days, wholesome thoughts were called kuśala-dharma, and unwholesome thoughts were called akuśala-dharma. We find that these two words were used for a long time in our ancient literature. Kuśala-dharma and akuśala-dharma are both Dharma. What one’s mind contains at this moment is Dharma—"Dhāretī ti dharma."

Two other words that occur in the ancient literature are ārya-dharma and anārya-dharma. As the centuries passed, the real meaning of these words has been lost. Today the word ārya is used for a particular race of human beings. In the India of those days, this meaning was nowhere to be found. Ārya had nothing to do with a race of human beings. Rather, it meant one who has a pure mind—one who is a noble person, a saintly person; one who has eradicated all the impurities of the mind. Such a one was called an ārya. One who lives the life of negativity, impurity, and generates anger, hatred, ill will, or animosity, was called anārya. So anybody whose mind contained purity was called ārya, and anybody whose mind contained impurity was called anārya.

Words like Hindu-dharma, Buddhist-dharma or Jain-dharma, were never used in our ancient literature. Other sects came much later, but even when these three were there, nobody used these words. The words kuśala-dharma and akuśala-dharma were used. Slowly, after a few centuries, another division came: kuśala-dharma (wholesome Dharma) was called dharma, and akuśala-dharma (unwholesome Dharma) was called adharma.

In the ancient scriptures, there was another definition of the word dharma: the nature or characteristic of what the mind contains, whether wholesome or unwholesome. What is the characteristic of the contents of one’s mind? This was called dharma. Its nature, its characteristic was called dharma. In Indian languages today, we still hear an echo of this meaning when someone says: "The dharma of fire is to burn." The nature of fire is to burn itself and to burn others. Similarly, we can say that the dharma of ice is to create coolness. This is the nature of ice.

What do these universal characteristics have to do with Hinduism? What have they to do with Buddhism, or Christianity, Islam, Jainism or Sikhism? Fire burns; ice cools. This is a universal law of nature. If fire does not burn itself and others, it cannot be fire. If it is fire, then its characteristic must be to burn itself and to burn others. The dharma of the sun is to give light and heat. If it does not give light and heat, it cannot be the sun. The dharma of the moon is to give a soft, cool light. This is the dharma, the nature of the moon. If it does not do that, it is not the moon.

This was how the word dharma was used in those days. If the contents of my mind are unwholesome—for example, if I am generating anger, hatred, ill will, or animosity at this moment—then the nature of these negativities is to burn. They will burn me. The vessel containing the fire is the fire’s first victim; then this fire and its heat start spreading to the environment around it.

It is the same when there is negativity in the mind. One who contains this negativity, who generates this negativity, is the first victim. He or she becomes very miserable. How can you expect peace, harmony and happiness, if you are generating anger? This is totally against the law of nature. That means it is totally against Dharma, which is the universal law of nature. If, knowingly or unknowingly, I place my hand in fire, my hand is bound to burn. The fire does not discriminate. It does not notice whether the hand belongs to a person who calls himself or herself a Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Jain, Sikh or Parsi, or an Indian, American, Russian or Chinese. There is no difference, no discrimination, no partiality; Dharma is Dharma.

In the same way, when my mind is generating purity, the negativities are eradicated. According to the law of nature, when the mind is pure, it is full of love, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity. This is the nature of a pure mind. This pure mind may belong to a Hindu or a Christian, or it may belong to an Indian or a Pakistani: it makes no difference at all. If the mind is pure, it must have these qualities. And when the mind is full of love, compassion, goodwill and equanimity, then again, the universal law is such that these contents of the mind have their own nature, their own Dharma. They give so much peace, so much harmony, so much happiness. One may keep calling oneself by any name. He may keep performing this rite or that ritual, this religious ceromony or that religious ceremony. He may have this external appearance or that external appearance. He may believe in this philosophy or that philosophy. It makes no difference at all. Dharma is Dharma.

The moment you defile your mind, the moment you generate any negativity, nature starts punishing you then and there. The punishment doesn’t wait until after death. Whatever happens after death will happen then. But what happens now? Anybody who generates anger now will experience nothing but unhappiness and misery. This person may have any name, may be from any caste, from any community, from any sect or from any country: it makes no difference at all. Because one has generated negativity, one is bound to suffer here and now.

Similarly, when you generate purity of mind, when your mind is full of good qualities such as love, compassion and goodwill, nature starts rewarding you here and now. You won’t have to wait until the end of your life—you start getting the rewards of a pure mind now. When your mind is full of love, full of compassion, you start experiencing so much peace, harmony and happiness. This is Dharma. It has nothing to do with sectarianism.

Someone who calls himself a very staunch Hindu, a staunch Muslim, a staunch Christian or a staunch Sikh, may be a very good Dharmic person, or may not have any trace of Dharma. Sectarian rites and rituals, sectarian beliefs or philosophies, sectarian religious ceremonies and outward appearances have nothing to do with Dharma. Dharma is totally different. Dharma means what your mind contains now. If what it contains is wholesome, it rewards you. If it is unwholesome, it punishes you.

If this understanding of Dharma becomes more and more prevalent in Indian society, as it was twenty-five centuries ago, then the country will be more peaceful because its people will be more peaceful. Everyone will give importance to whether or not he or she is a Dharmic person. That means, is one keeping one’s mind pure, free from impurities, free from negativities? If you keep generating anger, hatred, ill will, animosity and other negativities, you are not a Dharmic person. You may perform some rite or ritual. You may go to a temple and bow before a particular idol, or to a mosque to recite a namaz. You may go to a church to say prayers, or to a gurudwārā to chant kirtans. Or you may go to a pagoda and pay respect to the statue of Buddha. These do not help at all.

When you generate negativity in your mind, you may blame various outside reasons for your misery. You may find fault with others. You may be under the wrong impression that you are miserable because so-and-so abused or insulted you, or because something which you wanted has not happened, or because something that you did not want has happened. You remain deluded for your whole life that you are miserable because of these apparent external reasons. Because Dharma was lost to the country, we have forgotten to go deep inside to find the real cause of misery.

Suppose someone abuses me, and I become miserable. Between these two events, something very important happens inside me. But that link remains unknown to me. When somebody abuses me, I start generating anger and hatred; I start reacting with negativity. Only then do I become miserable, not before. The reason I am miserable is not because somebody has abused me, nor because something unwanted has happened. Rather, it is because I am reacting to these outside things. This is the real cause of my misery. You cannot understand this by listening to discourses such as this, by reading scriptures, by intellectualizing or accepting it at the emotional or devotional level. The real understanding of Dharma can only come when you start experiencing it within yourself.

To illustrate this point: suppose by mistake I have placed my hand in fire. The law of nature is such that the fire starts burning my hand. I take my hand away because I don’t like being burned. The next time, I again make a mistake and put my hand in the fire. Again, my hand gets burned, and again I take my hand back. I may do this once, twice, or three times, and then I start to understand: "This is fire, and the nature of fire is to burn. So I had better not touch the fire." This becomes a lesson, and I begin to understand at the experiential level that I must keep my hand away from fire.

In a similar way, one can learn how to practice Dharma using a technique which was very common in ancient India. To learn Dharma means to observe the reality within oneself. The word that was used for this was "vipassanā," which means "to observe reality in a special way." This means to observe reality in the right way, the correct way, to observe it as it is—not just as it appears to be, not just as it seems to be, not coloured by any belief or philosophy, not coloured by any imagination—but to observe it by working in a scientific way.

For example, when anger has arisen, you observe the reality that anger has arisen. Cutting yourself off from the external object of anger, you simply observe anger as anger, hatred as hatred; or passion as passion, ego as ego. You observe any impurity that has arisen on the mind. You simply observe it, observe it objectively, without identifying yourself with that particular negativity.

It is very difficult to observe objectively. When anger arises, it is like a volcanic eruption, and we get overpowered by it. When we are overpowered by anger, we cannot observe anger. Instead, we perform all the vocal and physical actions which we did not want to perform. And then we keep repenting: "I should not have done this. I should not have reacted in this way." But the next time a similar situation occurs, we will react in the same way, because we have not experienced the truth within ourselves.

If you learn this technique of observing the reality within yourself, then you will notice that, as anger arises in the mind, two things start happening simultaneously at the physical level. At a gross level—at the level of your breath—you will notice that, as soon as anger, hatred, ill will, passion, ego, or any impurity arises in the mind, your breath loses its normality. It cannot remain normal. It will become abnormal—slightly hard, slightly fast. And once that particular negativity has gone away, you will notice that your breath becomes normal. It is no longer fast, no longer hard. This happens in the physical structure at a gross level.

Something also happens at a subtler level, because mind and matter are so interrelated. One keeps influencing the other, and getting influenced by the other. This interaction is continuously happening within ourselves, day and night. At a subtler level a biochemical reaction starts within the physical structure. An electromagnetic reaction starts and, if you are a good Vipassana meditator, you will notice: "Look, anger has arisen." And then what happens? There is heat throughout the body; there is palpitation; there is tension throughout the body.

One need not do anything except observe. Do nothing; just observe. Don’t try to push out your anger. Don’t try to push out the signs of the anger. Just observe, just observe. Continue to observe, and you will notice that the anger becomes weaker and weaker, and passes away. If you suppress it, then it goes deep into the subconscious level of your mind. When it is suppressed, it does not pass away.

Whenever misery comes, we think that the cause of this misery is something outside, and we make a great effort to rectify external things: "So-and-so is misbehaving. I am unhappy because of this person’s misbehaviour. When this person stops misbehaving, I will be a very happy person." We want to change this person. Is this possible? Can we change others? Well, even if we succeed in changing one person, what guarantee is there that somebody else will not appear, who will again go totally against our desires? It is impossible to change the entire world. The saints and sages, enlightened people, discovered the way out: change yourself. Let anything happen outside, but do not react. Observe the truth as it is. But when we don’t know the technique of observing ourselves—the technique of self-realization, the technique of truth-realization—then we can’t work out our own salvation.

For example, you may try to divert your attention. You are very miserable and you can’t change the other person or the outside situation, so you try to divert your mind. You go to a cinema or a theatre, or worse, to a bar or gambling casino, to divert your attention. For awhile you may feel that your misery is gone. This is an illusion: you have not come out of your misery; it is still there. You have merely diverted your attention, and the misery has gone deep inside. Time and time again it will erupt and overpower you. You have not come out of your misery.

There is another way of diverting the mind, this time in the name of religion. You go to a temple, a mosque, a gurudwārā, or a pagoda, to chant or pray. Your mind will be diverted, and you may feel quite happy. But again, this is an escape. You are not facing your problem. This was not the Dharma of ancient India.

We have to face the problem. When misery arises in the mind, face it. By observing it objectively, you go to the deepest cause of misery. If you can learn to observe the deepest cause of misery, you will find that layers of this deep-rooted cause start getting eradicated. As layer after layer gets peeled off, you start to be relieved of your misery. You have neither suppressed your negativity, nor expressed it at the vocal or physical level and harmed others. You have observed it. Doing nothing, you have just observed.

This is a wonderful technique of India. Unfortunately, our country lost it because we lost the real meaning of the word dharma. Now these crutches, these scaffoldings of Hindu-dharma, Buddhist-dharma, Jain-dharma and Muslim-dharma have become predominant for us. When we say Hindu-dharma, then Hindu is predominant for us. Poor Dharma recedes behind the curtain into the darkness. Dharma has no value, because Hindu is more important. When we say Muslim-dharma, Muslim is important. When we say Buddhist-dharma, Buddhist is important; Jain-dharma, Jain is important. It’s as if Dharma is not an entity of its own. But what a great entity Dharma is! It is the law of nature, the eternal truth; and we are missing it when we give prominence to these false scaffoldings, crutches. We are forgetting the real essence of Dharma.

When someone starts giving importance to Hindu-dharma, he never gives importance to Dharma. Hindu-dharma and all the rites, rituals, ceremonies and appearances become more important for this person. He performs them and feels that he is a very Dharmic person. Similarly, if one gives importance to Muslim-dharma, Sikh-dharma, or Buddhist-dharma, one feels that he is a very Dharmic person. This person may not have even a trace of Dharma, because all the time his mind is full of impurity, full of negativity. What a great delusion it is when one feels that he is a Dharmic person because he has performed his rite or ritual; because he has gone to this temple or to that mosque; because he has gone to this church or to that gurudwārā; because he has recited this or recited that. What has happened to us? Where is this sectarianism leading us? Far away from Dharma!

The yardstick of Dharma should be: "Is my mind getting purified or not?" There is nothing wrong with performing a particular rite, ritual, or religious ceremony. There is nothing wrong with going to a mosque or a temple. But one should keep examining oneself to see: "Is my mind getting purified by performing all these rites, rituals and ceremonies? Am I getting liberated from anger, hatred, ill will, animosity, passion, ego?" If so, then yes, they are very good.

If no improvement is coming, then one sees that he is just deluding himself, fooling himself: "Even if my mind appears to be purified for a short time, I am deluding myself, because I have not come out of my misery, my impurities. My impurities lie at the deepest unconscious level of my mind. That is the storehouse of my impurities." We carry this storehouse from life to life, from life to life. And we either give more input, more impurities, or we remove them.

Mostly we keep giving more and more input, and therefore we become more and more miserable. How can we purify the deepest level of the mind? We can purify the surface of the mind to some extent by intellectualizing, or by devotional or emotional beliefs. But to take out the impurities from the deepest level of the mind, we have to work—and work in the way that nature wants us to work. The law of nature says that whenever we generate any impurity, the source of the impurity lies at the deepest level of our mind. And the deepest level of our mind is constantly in contact with body sensations.

Day and night, whether you are asleep or awake, the deepest level of your mind (the so-called "unconscious") is never unconscious: it is always feeling sensations on the body. Whenever there is a pleasant sensation, it will react with craving—rāga, rāga. Whenever there is an unpleasant sensation, it will react with aversion—dveśha, dveśha. Craving, aversion, craving, aversion: this has become the behaviour pattern of the mind deep inside. Twenty-four hours a day, day and night, every moment there are sensations in the body deep inside, and at the deepest level the mind keeps reacting. It has become a slave of its own behaviour pattern. Unless we break that slavery, how can we come out of our misery? We will be just deluding ourselves by trying to purify the surface of the mind, while we forget the deep root. As long as the roots are impure, the mind can never become pure.

Vipassana is a technique of India. Laudable references to Vipassana are given in the ṚgVeda. The most ancient literature of this country is full of words of praise for Vipassana:

Yo viśvābhih vipaśyati bhuvanah sañca paśyati sa na pārśadati dviśah.

-One who practices Vipassana in a perfect way—‘sañca paśyati, sa na pārśadati dviśah’—comes out of all aversion and anger; the mind becomes pure.

But one has to practice it oneself. If you just keep reciting this verse of the Ṛg Veda, how is this going to help? Suppose you keep reciting: "The cake is very sweet; the cake is very sweet." How can you taste the sweetness of the cake unless you put it in your mouth? The practice of Dharma is more important than merely accepting Dharma at the intellectual, emotional or devotional level. And this practice is Vipassana.

In ancient days, Vipassana was everywhere in India. A traveller came from Burma then. Travelling the whole country, he found that in every household people were practicing Vipassana. He visited different households, rich and poor, and found that not only the husband, wife and children, but even the servants were practicing Vipassana every morning and evening. And everywhere there was talk of Vipassana, because people were getting benefit from it. Over time, unfortunately, in this country we became involved in rites, rituals and religious ceremonies and forgot this scientific understanding of Dharma.

Dharma is nothing but a pure science, a super-science of mind and matter: the interaction of mind and matter, the cross-currents and the under-currents happening deep inside every moment. Things are happening inside every moment, but we remain extroverted, giving importance to things outside. Say somebody has abused me, and I don’t have this practice of observing what is happening within myself: I become angry and start shouting. What am I doing?

When someone is abusing me, it is that person’s problem, not mine. If they are abusing, it means that they are generating negativity in the mind. This person is a sick person, an unhappy person, a miserable person when he is generating anger and shouting. Why should I generate anger? Why should I shout and make myself miserable? This understanding cannot come unless you have experienced it. It is like the experience when you touch fire and learn not to touch it again. It happens once, twice, several times, and then you learn not to touch fire again. Similarly, you can develop the ability to observe what is happening inside. Anger has arisen and you will immediately notice that there is fire, and it has started burning you: "Look, I am burning! I don’t like burning. Next time I will be more careful." Or, "Oh no, here is anger. If I generate anger, I’ll burn." By mistake you have again generated anger; again you observe it. Again you generate anger, and again you observe it. After a few experiences, you start coming out of it.

But when you are not observing the reality within yourself, then you give all importance to the apparent external cause of your misery, trying to rectify that. For example, a mother-in-law says: "Our household is a real hell now." If you ask her the reason, she says: "It is all because of this daughter-in-law. What a daughter-in-law has come into our house! She is so modernized. She goes totally against all our traditions and beliefs! She has spoiled the entire harmony of the household." If you talk to the daughter-in-law, she will say: "The old lady should change a little. She doesn’t understand that there is a generation gap. The times are changing. Why doesn’t she understand? She is making herself and everybody else miserable." The daughter-in-law wants the mother-in-law to change. The mother-in-law wants the daughter-in-law to change. The father wants the son to change. The son wants the father to change. This brother wants the other brother to change. The other brother wants this brother to change.

"I won’t change. I am perfectly all right. Nothing in me needs changing!" We never see within ourselves that we are not perfectly all right, that we are the cause of our own misery. The basic problem lies within ourselves, not outside. We start realizing this at the experiential level by practicing Vipassana. It is very difficult to observe abstract anger. Even for a Vipassana meditator, it takes a long time before one reaches the stage where one can observe abstract anger, or abstract passion, abstract fear, abstract ego. It is very difficult.

When anger arises, along with it, a sensation starts in the body. Along with anger, the breath also becomes abnormal. You can observe this. Even in ten days you can learn this technique. By coming to a Vipassana course and working properly, you can understand how to observe the breath. Perhaps anger has come, and you can’t observe abstract anger, but you can observe your breath: "Look, the breath is coming in and going out." This is not a breathing exercise. You just observe the breath as it is—if it is shallow, it is shallow; if it is deep, it is deep; if it passes through the left nostril, then the left nostril; through the right nostril, then the right nostril. You simply observe it. Or perhaps there is heat throughout the body, or palpitation, or tension. You just observe them. It is easy. These things become easy to observe if you practice even for one or two ten-day courses.

To observe anger as anger, or hatred as hatred, or passion as passion, is very difficult. It takes time. That is why the wise people, the enlightened people, the saints and seers of India advised: "Observe yourself." Observing oneself is a path of self-realization, truth-realization—one can even say "God-realization," because after all, truth is God. What else is God? The law is God, nature is God. And when one is observing that law; one is observing Dharma. Whatever is happening within you, you are just a silent observer, not reacting. As you observe objectively, you have started taking the first step to understand Dharma; the first step towards practicing Dharma in life.

By practicing Dharma, you won’t run away from external activities like going to this or that temple, or performing this or that rite or ritual. But at the same time as you are doing these things, you will start observing the reality pertaining to your mind at that moment: "What is happening in my mind at this moment? Whatever is happening in my mind from moment to moment—this is more important for me than anything that is happening outside." You will start to notice how are you reacting to things outside. Whenever you react, this reaction becomes a source of misery for you. If you learn not to react but simply to observe, you will come out of the suffering. Of course it takes time. One does not become perfect immediately, but a beginning is made.

Let a beginning be made to understand Dharma. Dharma is free from all sectarian beliefs, dogmas, rites and rituals. Even sectarian names are not necessary. You may or may not call yourself a Hindu or a Muslim, but you should be a Dharmic person, a person living the life of Dharma. This means that your mind should remain pure. If your mind remains pure, then all your other actions, vocal or physical, will naturally become pure.

Mind is the base. When the mind is impure, full of negativities, then our vocal actions are bound to be impure, and our physical actions are bound to be impure. We have started harming ourselves. We have started harming others. As I said, when you generate anger, or hatred, or ill will, you are the first victim of your negativity. You become very miserable, and the misery that you generate because of your negativity starts to permeate the atmosphere around you. The entire environment around you becomes so tense. Anyone who comes in contact with you at that time becomes tense, miserable. You are distributing your misery to others. This is what you have, and you keep distributing it to others. You are making yourself miserable, and you are making others miserable.

On the other hand, if you learn the art of Dharma—this means the art of living—and you stop generating negativity, you start experiencing peace and harmony within yourself. When you keep your mind pure, full of love and compassion, the peace and harmony that is generated within permeates the atmosphere around you. Anyone who comes in contact with you at that time starts experiencing peace and harmony. You are distributing something good that you have. You have peace, you have harmony, you have real happiness, and you are distributing this to others. This is Dharma, the art of living.

In ancient India, Dharma was nothing but an art of living, the art of how to live peacefully and harmoniously within, and how to generate nothing but peace and harmony for others. And to achieve that, proper training was given. There were Vipassana meditation centers in practically every village. Vipassana centers were everywhere, as were yoga schools, yoga colleges and yoga hospitals. They were a part of life. Students used to learn this art in their schooling. Practicing it, they lived good lives, healthy lives, harmonious lives.

May that era come again. May people understand what Dharma is. May you be released from the demons, the devils, of sectarianism and communalism which make you forget all about Dharma. May you come out of this suffering. May you live a real life of Dharma, so peaceful, harmonious and happy for you and so peaceful, harmonious and happy for others.

May all of you who have come to this Dharma talk find time to spare ten days of your life to learn this technique. You will get the benefits here and now. It is not necessary for you to convert yourself from one organized religion to another organized religion, from one sect to another sect. Let a Hindu keep calling him or herself Hindu for the whole life. Let a Christian keep calling himself Christian for the whole life—a Muslim, Muslim; a Sikh, Sikh; a Buddhist, Buddhist. But one should become a good Hindu. One should become a good Muslim, a good Christian, a good Sikh, a good Buddhist. One should become a good human being. Dharma teaches you how to become a good human being, how to live a good life, a happy life, a harmonious life.

May all of you get trained in this wonderful technique. Come out of your misery and enjoy real peace, real harmony, real happiness. Real happiness to you all. Real happiness to you all.